In his blog ‘The Voices Within’ for Psychology Today, HtV’s Charles Fernyhough writes:

In his blog ‘The Voices Within’ for Psychology Today, HtV’s Charles Fernyhough writes:

In my last post, I noted that public perceptions of voice-hearing (due in part to distorted media representations) get the science of voice-hearing very wrong. In a new article1, we have reviewed the evidence around whether voice-hearing is always a sign of mental illness. The paper is published in the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin, and it is open access, meaning that you can read it for free here.

Our review stems from a working group of the International Consortium on Hallucination Research, which was founded in 2011 with a view to intensifying research into fascinating and often troubling experiences like auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs). Drawing together academics and clinicians from the UK, Norway, Germany, Italy, Australia, Belgium, and the Netherlands, the working group set out to understand the state of research into AVHs that occur in individuals who do not need psychiatric care. The group presented their findings at a meeting in Durham, UK, in September 2013.

The idea that voice-hearing can be a part of normal experience is not a new one. At the end of the 19th century, the London-based Society for Psychical Research asked the following question of 17,000 members of the public: had they ever, when awake, had the impression of seeing or hearing or of being touched by anything which, so far as they could discover, was not due to any external cause? Around 3% of respondents reported having heard voices. A recent review of such surveys showed that population rates of AVHs have varied between 0.6% and 84%, depending on the exact question being asked. A best guess is that around 5-15% of the population have had infrequent or one-off voice-hearing experiences, with about 1% having more complex and extended voice-hearing experiences in the absence of any need for psychiatric care.

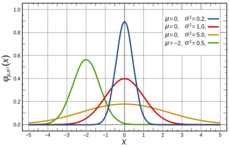

One way of making sense of these findings is in terms of the idea that unusual experiences like voice-hearing exist on a continuum that connects normal experience to psychiatric symptoms. The idea is that hearing voices is something that happens to all sorts of people, and all of us are prone to it to a greater or lesser extent. In our paper, we consider whether there might actually be two kinds of continuum at work.

One has been termed a continuum of experience. The idea is that voice-hearing exists at one end of a spectrum that includes everyday experiences like day-dreaming and intrusive thoughts. The other continuum is a continuum of risk, on which people differ in their risk of developing problems resulting from these experiences. The evidence for the commonness of voice-hearing experiences points to a continuous distribution in the typical population (that is, a smooth curve, rather than a categorical break between groups of people). Evidence for the second continuum, though, is less clear-cut. It may be that there are some types of people who are prone to develop distressing psychotic experiences, and thus ending up needing care.

We also reviewed similarities and differences between the experiences reported by those who seek help with their voices, and those who don’t. The two groups don’t differ very much in what their voices are like, in terms of loudness, location, number of voices, personification, etc. The voices of those who seek care tend to be more unpleasant and more frequent, and voice-hearers in this group feel less in control of them. Intriguingly, there is no real evidence that neural processes underlying the voice-hearing experiences differ between the two groups. On the basis of current evidence, voices seem to work in the brain in the same way, whether you seek care or not.

There is much more to be learned about the voices heard by people in nonclinical groups. One intriguing finding is that voices in those who don’t seek care appear earlier in life than more distressing ones. You might expect the opposite: that people who are most troubled by their voices will have been putting up with them for longer. Very little data exist on the timecourse of AVHs over the lifespan, and this interesting finding needs to be confirmed by further research.

So what are we to make, then, of the clinical significance of voice-hearing? One view is that voice-hearing can be likened to a cough: something which could be a symptom of a deeper problem, but often isn’t. That’s a useful way of thinking about it, but it doesn’t quite work. As the work of the Hearing Voices Movement has shown, people enter into relationships with these experiences; their voices have personal significance for them. Coughs do not figure in people’s acts of meaning-making in quite the same way.

Astonishingly, the latest edition of the ‘psychiatrist’s bible’, DSM-5, appears not to recognise this evidence for the continuity of hallucinatory experiences. Its wording (pp. 87–88) implies that hallucinations may be considered within the range of normal experience only if they occur on the fringes of sleep (so-called hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations), or if they occur as part of religious experience in certain cultural contexts. American psychiatry is heavily invested in the idea of schizophrenia as a progressive brain disease, and voice-hearing is often seen as the cardinal symptom of that (vigorously contested) psychiatric category. Rather than evaluating the evidence for nonclinical hallucinatory experiences, the authors of DSM-5 have simply ignored it.

Voice-hearing is part of normal experience for many people. That is not to say that it cannot also be extremely distressing and a cause for people to seek help. The sooner we come to appreciate that voice-hearing is something that happens to people, rather than merely a symptom of a diseased brain, the sooner we will close in on a genuinely humane and enlightened understanding of the experience.