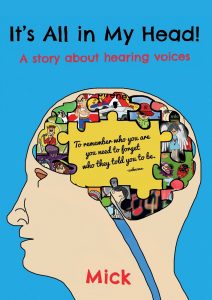

In this article, Arya Aryan reviews It’s All in my Head! by Mick, ‘the story of a normal Dutch guy who hears voices inside his head other people can’t hear’.

Emotional, intimate, humorous, compassionate, sincere and democratic, It’s All in my Head is Mick’s account of the stories that the voices he hears have to tell and share with us. This is a book about both the voices’ stories and Mick’s experience and struggle with them, as well as his journey on the road to agency and recovery. It is a journey from being a passive object to which things happen – ‘things are being destroyed’ (115) – to possessing some degree of agency – ‘I made it’ (151). A similar to the Unnamable’s ‘I invented it all’ (117) – though the voices still have their own ontologically autonomous status. It is a very thought-provoking, insightful memoir into the nature of auditory verbal hallucinations, the process of storytelling and its therapeutic function.

Emotional, intimate, humorous, compassionate, sincere and democratic, It’s All in my Head is Mick’s account of the stories that the voices he hears have to tell and share with us. This is a book about both the voices’ stories and Mick’s experience and struggle with them, as well as his journey on the road to agency and recovery. It is a journey from being a passive object to which things happen – ‘things are being destroyed’ (115) – to possessing some degree of agency – ‘I made it’ (151). A similar to the Unnamable’s ‘I invented it all’ (117) – though the voices still have their own ontologically autonomous status. It is a very thought-provoking, insightful memoir into the nature of auditory verbal hallucinations, the process of storytelling and its therapeutic function.

Being Mick’s first attempt at writing stories, the book has a structure which is not typical of autobiographies. It opens with a foreword by Dr Dirk Corstens, Mick’s psychiatrist who helped him through the journey of recovery. In the introduction, Mick recounts the genesis of writing the book. This is followed by chapter-like sections, each starting with the drawing in colour and name of a character, which is a voice that Mick has been hearing.

The first voice is also his most favourite, the Voice of the Sweet Old Lady. Mick’s granny was an unconditional source of love and protection who would come over to take care of him. Unfortunately, granny became sick and died just before Mick’s final exam. Almost on the same day, Mick started to hear ‘a very friendly voice of an old lady’ (14).

The second voice is ‘The Most Rude One’. As Mick did not know how to cope with course evaluations and ‘mental turmoil’ (21), he retreated into a fantasy world and told his mentor made-up stories. As thoughts of suicide struck Mick, he heard the voice of a man yelling ‘why don’t you jump?’ (23). At this point, Mick started to hurt himself. After putting a smile on the face of the reader, Mick turns to the ghastly and heart-breaking story of ‘The Howling Dog’, a voice he started to hear after his dog had its throat violently cut by Mick’s mother before his eyes.

Lesley is the next voice the reader is acquainted with. This part of the memoir is filled with sincere feelings, passion, humour and cuteness. Lesley is a very cute, loving, and caring character who takes the ‘things she hears very literally’ (47). For example, ‘if someone said that it is raining cats and dogs outside, Lesley would run to the window and start looking hopefully for cats and dogs falling from the sky’ (48).

Conijntje, the next voice, is a nasty rabbit who commands Mick to hurt himself (56). At the clinic Mick was locked up for three weeks in a room where there was a mural of Miffy, a little rabbit character, on the wall. Then, that the idea of drawing Conijntje struck Mick’s mind. There are other voices worth reading about. Then, Mick also tells us he is ‘transgender’ (107). The narrative ends with an epilogue in which Mick tells us about how useful writing this book has been in helping him discover many underlying issues about the voices and himself. The final acknowledgements reflect the book’s unconventional structure and use of language and are more metafictive in nature, concluding with Mick’s gratitude to the voices.

Given my own passion on the subject and research interest, I can pinpoint a few major themes in the book. The drawings add to the childlike sincerity of the tone and help Mick to freely express his emotions and feelings. By visualising and embodying the voices and making them look funny, humorous and sometimes adorable, the drawings mitigate the creepiness and uncanniness of the voices which might otherwise be ontologically threatening (as unlocatable voices pose a threat to the person’s existential security). Both drawings and characterisation via storytelling re-locate and incarnate the disembodied voices that at times carry immense authority and are eerie – an idea developed by Steven Connor in Dumbstruck (2000, 20). As they do not echo the person’s underlying intentional state, they are viewed as autonomous and authoritative. Such voices intensify existential insecurity to the extent of a total annihilation, as in the case of some voices’ suicidal commands. Professor Julian Leff’s ‘avatar’ therapy, initiated in 2014, is an indication of this method in helping voice hearers deal with malicious, destructive voices. Yet, as Mick ‘could not include their whole story inside one drawing’ (9), writing came to his aid. Writing (storytelling), by creating fully-fledged characters out of the voices and telling their stories, helps the voices acquire a kind of quasi-corporeality, not unlike Connor’s concept of ‘the vocalic body’ (35). Storytelling re-integrates a dissociative self that would otherwise be subject to annihilation. This is a valuable insight that this book provides as do other writers – Charlotte Brontë, Virginia Woolf and Hilary Mantel. As Mick puts it: ‘I now know who I am’ (8), similar to Hilary Mantel’s words in Giving up the Ghost (2003): ‘sometimes I feel that each morning it is necessary to write myself into being’ (222). Having said that, the book helps re-fashion our understanding of the self from a core, unified entity to a more democratic space in which multiple voices/selves cohabit.

It is worth noting that autobiographical references help Mick avoid losing complete touch with reality and create what Louis A. Sass in Madness and Modernism (1992) calls ‘double-bookkeeping’, a state in which the voice hearer lives simultaneously in the real world and a solipsistic one generated and projected by one’s own consciousness.

We need to reconsider our understanding of the nature of auditory verbal hallucinations. Unlike much of the emphasis among experts such as Connor and Sass on the threatening aspect of unlocatable voices, we realise that some of Mick’s voices are nice from the beginning. Not all Mick’s voices fall into the category of Connor’s ‘bad voice’. Perhaps Connor’s definition of the bad voice as belonging to the other (and therefore eerie) could be re-fashioned.

As R. D. Laing has it, ‘madness’ could ‘also be break-through’. Thus, hearing voices, though not necessarily a sign of madness as the book suggests, can be an exceptional ability, a gift, that, if put to use artistically, would create beautiful works of art that work on our empathic and sympathetic ability.