Today’s post is authored by Aimee Wilson, a 27 year old mental health blogger. Her Blog is called ‘I’m not Disordered’.

Today’s post is authored by Aimee Wilson, a 27 year old mental health blogger. Her Blog is called ‘I’m not Disordered’.

Aimee writes:

In celebration of World Mental Health Day, I’m honoured to have been invited to write this book review. This new found emphasis on engaging with ‘Experts by Experience’ has resulted in a huge improvement of Services. Emily’s Voices is the epitome of capturing the importance and significance of working alongside people with lived experience.

The book begins with a forward by Dr Susan Shaw who talks about how ‘voice-hearing is a phenomenon which is poorly understood…’ and discusses the possibilities in voice-hearing and how an individual can experience the ‘phenomenon’ completely differently to another. With that in mind, it’s estimated that 15% of adults will hear a voice at some point in their life but not everyone will experience this as a frequent event and may not seek help for it.

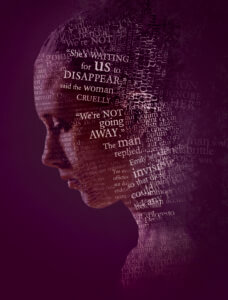

The prologue (titled The Hospital) begins with quotes from Emily’s auditory hallucinations; I found this incredibly insightful. Hearing voices is something that’s very hard for others to understand – even those who have also experienced hallucinations – but to tell you what they are saying… well, it makes it easier to understand. Easier to empathise. Possible to empathise. Unfortunately, Emily hears more than one voice and expressed her fear that these voices belonged to real people who were following her: ‘Three people watching me. There’s no space of my own now to retreat to.’

The rest of the book is divided into chapters within ‘Parts’ – with Part One titled ‘Kent.’ Emily begins by talking about her early life and upbringing in a ‘leafy, picturesque village in Kent.’ She talks about being raised by a Mum who was constantly in volatile relationships, and, instead, spending more time with her Grandparents who were kind, and loving people. Towards the end of the Part, Emily talks about the difficulties she began experiencing with her weight after children at School called her ‘fatso.’ After being hospitalised for Anorexia, Emily was struggling to eat a meal when she heard a voice for the first time; it told her that she knew she had to eat.

Part Two is titled ‘London’ and begins with Emily hearing voices again whilst working as an au pair, which she later refers to as ‘the worst decision that I ever made.’ In this part, Emily discusses her experiences with talking to a friend and how she felt conflicted in whether to tell this person whom she’d trusted for years, or keep her voice hearing a secret for fear of him thinking she were ‘crazy.’ Emily talks about feeling unable to relax around two of her other friends and so she had to take ‘care to hide how frightened I felt at the voices.’ This, and her experiences with her employers when they questioned whether she heard voices really illustrated the stigma surrounding voice-hearing – as a fellow sufferer, it’s something that I think needs more attention as usually, the media only covers the stigma around mental health in general. And that is very different, and it’s great to have a book that recognises that.

Part Three is titled ‘Oxford’ and begins with Emily attending a Mind day-centre and finding another service user who convinced her to study her AS-level in Psychology. A few pages later, and Emily is referred to a therapist who begins their work together by discussing diagnosis as ‘labels’ and finding the absence of them helpful with them only really being useful to clinicians. A really positive sign when Emily is sat in the therapist’s office was that she could no longer hear the voices; something that’s often common when a person hallucinating enters a safe space. Emily’s question of whether the therapist can help ‘get rid of the voices’ really resonated with me and my desperation to do all I can to stop the hallucinations. Emily later discusses her own condescending worries about the fact that she was volunteering at twenty-five years old and saw the absence of having a ‘proper job’ as a stark reminder of her mental illness. I’ve often wondered what I’d done with my life whilst all of my friends are graduating from University and getting married and having children, but I’ve learnt to be kind to myself and recognise that I have still made some achievements. The therapist later points out that Emily’s recognition of the voices being repetitive in their trying to say that Emily is a ‘mental patient’ and needs to ‘take pills’ is a small achievement.

After a drunken talk with a fellow mental health sufferer, Emily sent her Mum a text that she wanted to end her life and was subsequently taken to Hospital by Police. In Hospital, Emily was told she has a Borderline Personality Disorder and spent three weeks attending Alcoholic Anonymous meetings where she met her Sponsor who taught her that alcohol makes problems worse.

‘I managed a smile. “I guess so,” I said. “I just wish that it felt easier than it is. Sometimes I feel that I’m in a power struggle with the voices. It’s them against me, and I have to win.”

“A power struggle is an interesting way of looking at it,” said Daphne, smiling at me.

“Well that’s what it feels like,” I replied. “I only hope that I’m going to win.”

A new discussion about one of Emily’s symptoms took place between herself and her therapist when they began discussing her fear of abandonment; particularly with male figures in her life. Having had her Father disappear, her step-father be violent and her loving Grandfather pass away, Emily seemed to have difficulties trusting men and was aware of becoming co-dependent on a man. Opening up about her childhood, and cutting out alcohol meant that Emily had better concentration for her Masters at University and she was offered the opportunity to get in touch with a Researcher conducting a project in voice-hearing. Through the research project, Emily’s confidence grew and she soon found herself meeting her Father. From personal experience, my back instantly went up when I read this and I was concerned that her situation might play out the same as my own and end in a deterioration of her mental health. In fact, the meeting was a ‘disaster’ but with her ongoing work to focus on and the support of friends, Emily got through the realisation that she didn’t want to know her Father.

Emily then goes onto discussing her meeting with ‘Angela’ who worked for the organisation Time To Change and their first conversation about the stigma that surrounded voice-hearing and the lack of people willing to speak up about their own experiences because of this. They talked about the fact that voice-hearing can be experienced with people with different diagnosis – a fact that I’ve recently experienced with an A&E Doctor assuming that it only happened to those with schizophrenia. “I wish the public knew that” Emily says.

In Chapter Seventeen, Daphne (Emily’s therapist) makes the statement that she no longer thinks that Emily is a Service User. Initially, this ‘throws’ Emily and she explains that she refers to herself as one during her research into voice-hearing and that she still hears voices, takes medication and has therapy. “But if I’m not a Service User, what do I call myself?” Emily asks Daphne.

When Emily’s Granny finally passed away, she learned that she can ‘feel fragile inside at times’ but that she can still maintain her equilibrium.

Note: Many of the names and identifying characteristics of people and places have been changed. Emily’s experiences are based on real life events.

You can buy Emily’s Voices (Emily Knoll) from Amazon, or from Blackwell’s Bookshop in Oxford.