Dr Jennifer Hodgson, lead researcher on our Writers’ Inner Voices study, writes:

The students I teach, although very able literary critics, sometimes need reminding that the characters in the books that they are interpreting are not, in fact, real people. It’s very easily done. Even the most sophisticated reader, when faced with the vivid and oversized inhabitants of fictional worlds, can easily become, as William H. Gass puts it a little bluntly in his essay “The Concept of Character in Fiction” (1971), a ‘gullible and superstitious clot’.

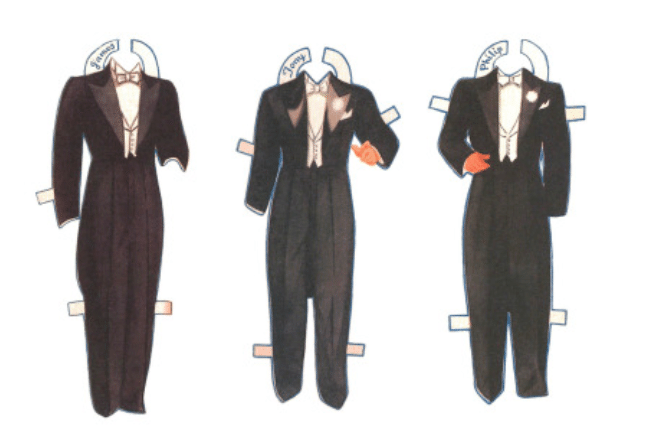

We are all apt to forget at times that the startling likeness between fictional characters and human beings is only analogous – that these are paper people, not real ones. ‘Fiction’s fruit survives its handling and continues growing off the tree’, writes Gass. Where the text is silent we nonetheless attempt to infer characters’ histories, speculate upon their motivations, diagnose precisely what it is that ails them. In the margins of my students’ essays I scribble the occasional reminder that characters are merely assemblages of words with human shape. Gass, no doubt, would do similarly. He writes that ‘nothing whatever that is appropriate to persons can be correctly said’ of characters.

But nonetheless characters persist in exerting their peculiar affective power upon us. We cannot resist making moral judgements of them, identifying with them – even writing new stories, fan fictions, to explore their existence beyond the original text from which they sprung. Characters, then, cannot be real, but they most certainly can be ‘real’. This is, of course, how fiction works: by building worlds and birthing people that we know to be false but temporarily accept as ‘true’. And so, whilst I’ll continue to steer my students towards only attending to what’s actually there in the text, the means by which what’s actually there in the text produces such a powerful imaginative response in readers, and how writers create such effects, is certainly worth thinking through.

Our study indicates that writers themselves share the illusion. Just as through reading we feel we come to ‘know’ people who momentarily seem ‘real’, many of the authors we interviewed spoke of the writing of characters not as a process of creating them but becoming acquainted with them through language. One writer detailed how she ‘writes into’ a character, likening the experience to ‘getting to know a friend’. Another spoke of their characters as being ‘like someone you know well’, saying he is ‘conscious of them as real people’. They commented too on the importance of characters feeling alive and autonomous. The vast majority described the success of their characters as being dependent upon how ‘real’ they feel: ‘I’ve got to build the character strong enough that the character feels real enough’, one commented.

Readers’ strange intimacies with fictional characters are not surprising. After all, through the novelistic depictions of their lives we come to know characters so well – better than we know one another, certainly, and perhaps better than we know ourselves. Novels have the special capacity to reveal what is impossible to know in real life: the unspoken perceptions, thoughts and feelings of another. For many critics, this paradox is what constitutes the distinctiveness of fiction. They argue that it is fiction’s facility to create these bloodless beings that nonetheless appear to be richly delineated and psychologically coherent individuals that makes the form so compellingly lifelike. E.M. Forster’s famous distinction between ‘round’ characters (complex, with psychological depth, capable of transformation) and those that are ‘flat’ (archetypal, caricatured, expressive only of a single idea) is still influential. In their recent book The Good of the Novel (2011), Liam McIlvanney and Ray Ryan argue that ‘[n]ovelistic truth… has to do with character’ and ‘the novel’s key strength is the disclosure of interiority’. For Forster a mixture of the two is necessary for fiction – Dickens is only a ‘good but imperfect’ writer because of what Forster sees as his overuse of characters that tend towards the flat.

Interestingly enough, his distinction is borne out by our study. There were marked differences in how the novelists we interviewed experienced their primary and secondary characters. The vast majority of the writers we interviewed said they experience their protagonists as having a complex interior life and in some cases a rich existence beyond the specificities of the plot in which they find themselves. Secondary characters, however, tend to develop more pragmatically, coalescing as and when necessary to the thrust of the narrative and were generally only experienced visually.

Nevertheless, it’s worth noting that throughout literary history, many writers have sought to develop alternative versions of personhood in fiction. The idea that with literary modernism came a new conception of the self not as unified and integral but centreless, fragmentary and dispersed is a familiar one. But the long history of the novel is awash with ‘flat’ characters who challenge conventional conceptions about what it is to be a self, as this recent article in the New Yorker explores. Some of the most interesting contemporary writing presents a vision of selfhood as affectless and opaque, totally devoid of essence, presence or unity. Recent notable examples include Tom McCarthy’s Remainder (2005), Ben Lerner’s 10:04 (2014) and Teju Cole’s Open City (2011).

Many of the innovative writers of the mid-twentieth-century were especially eager to debunk the notion of the ‘rounded’ character and, by extension, the illusion they perceived fiction as propagating that another human being could ever really be known. In the novels from this period by authors like Elizabeth Bowen, Henry Green, William Sansom, Muriel Spark and Ivy Compton Burnett, characters are indefinable, inexistent, centreless husks of people. Spark’s brilliant ur-metafiction, The Comforters (1957), is a prime example. In the novel, the main character, Caroline, ‘hears’ a typing ghost composing the action of the novel as she lives it and one minor character, Mrs Hogg, simply disappears upon fulfilling her function. To underline the point, one-third of the way through the book Spark issues the following disclaimer: ‘at this point in the narrative, it might be as well to state that the characters in this novel are all fictitious, and do not refer to any living persons whatsoever’. Compton-Burnett, another writer who resolutely refused to invite readers into the consciousnesses of her characters, issued a similar caveat when reflecting upon her own novels:

People in life hardly seem to be definite enough to appear in print… I believe that we know much less of each other than we think, that it would be a great shock to find oneself suddenly behind another person’s eyes. The things we think we know about each other, we often imagine and read in.

Writers such as these take great pains make the make the boundaries between fiction and life absolutely clear. Many of them argue that by doing so they offer a more lifelike rendition of what it is to be a self. For others, however, it is this rendering of the inner life that at once sets narrative prose apart from reality whilst providing a portal via which readers can immerse themselves in fictional worlds. For just as fiction makes imaginary people seem alive and vital, so too it makes those worlds seem solid and somehow ‘real’.

Elaine Scarry’s study of the literary imagination, Dreaming by the Book (2001), explores the techniques novelists use to set forth and substantiate the worlds of fiction. In the book she argues that writers of narrative prose vivify the images of the imagination by mimicking the structures of perception – how and why the objects of the real world look, sound and feel the way that they do. Fiction, Scarry argues, is a set of instructions for imagining a world. And as such, its capacity to reflect the inner life is crucial. Novels invite their readers not just to imagine a world, but to imagine what it is like to experience it. In fiction, there is always someone through whom the world is perceived, someone who holds the point of view – although it’s worth reminding ourselves that this needn’t be the same as the person doing the narrating.

Our study indicates that a kind of empathic throwing of the imagination plays an important role in creating this lens through which a story is communicated. The majority of the writers we interviewed said that they have the sense of inhabiting the interior world of their protagonists and ‘looking out through their eyes’. One writer commented that experiencing their character was like ‘wriggling down inside them’ and ‘thinking how would this feel?’ Another said of a particular character ‘she was not an external person that I could see, I would have a hard time describing her. I had a visual sense of absolutely everything else, the landscape, the other characters, but not her because I was inside her.’ For one the process is ‘like I’m sort of writing in her head… just behind her eyes or something, or I’m up in her head so I can hear her voice’.

This article first appeared on the blog ‘Writers’ Inner Voices‘ on 28 September 2015.