Dr Gary Sidley is a freelance writer and trainer who, in 2013, opted for early retirement from his post of Professional Lead/Consultant Clinical Psychologist after 33 continuous years of employment in mental health services. He writes on a range of topics, including alternatives to biological psychiatry (his book, Tales from the Madhouse: An insider critique of psychiatric services, was published by PCCS Books in February 2015 and is available from the publisher’s website here.)

In this blog post, Gary reflects on Voices, Visions and Other Unusual Experiences: The Challenges of Being a Mental Health Nurse – a two-day programme of events recently hosted by Hearing the Voice, which was designed to explore the challenges faced by those working in and using mental health services. He writes:

On the morning of the 8 April 2015 I embarked on the 140-mile drive from my Lancashire home to Durham University to participate in the conference, titled ‘Voices, Visions & Other Unusual Experiences – The Challenges of Being a Mental Health Nurse’. Now, three days after my return, I would like to share my personal reflections on the event.

My wife, Sue, accompanied me on this pilgrimage to the North East. Both of us had recently opted for early retirement from employment within the NHS psychiatric arena after 33 years of continuous service – Sue as a qualified nurse and I, for the most part, as a clinical psychologist. As such, we opted to arrive in Durham a day early and grasped the opportunity to explore the locality: a stroll along the banks of the River Wear; listening to live music in the town square; absorbing Durham’s illustrious history via the charming museum; and relishing the imposing sights of the castle and cathedral – all enjoyed under blue sky and warm sunshine.

And then the conference itself. On the first day we benefited from punchy, 15-minute presentations, both from people with lived experience of mental health problems and psychiatric professionals. Rachel Waddingham and Fiona MaCallum shared their recovery stories, highlighting the ways in which professional staff, at various times, both hindered and enabled their search for peace and emotional equilibrium. Powerful, often moving and occasionally humorous, their stories demonstrated the resilience of the human spirit as well as proving that emotional healing is always possible, irrespective of the depth of despair. Also, an emerging theme from these accounts was that the more therapeutic service responses tended to involve a staff member showing flexibility and a willingness to deviate from orthodox practice – for example by conducting an interview under a tree in Rachel’s garden!

From a professional perspective, Valentina Short and Paul Veitch provided stimulating and thoughtful accounts of their psychiatric-nursing journeys stretching over three decades, and their struggles with some ethical dilemmas inherent to the role of a mental health professional. For example, Paul shared his deliberations around operating as an approved clinician under the auspices of the Mental Health Act, and whether it was feasible to be involved in coercion while preserving a therapeutic relationship with the service user. And I chipped in with a brief presentation about stigma and why psychiatric professionals might be responsible for perpetuating it.

The delegates heard two notable examples of ground-breaking practice. Peter Bullimore described the Maastricht Interview for people with unusual experiences and beliefs, emphasising the importance of exploring the life events which may have contributed to their emergence; ‘everyone wants to be asked, even though not everyone will want to disclose’.

Russell Rassaque, the last speaker of the day, outlined the UK multi-centre pilot to evaluate the effectiveness of Open Dialogue in the management of acute psychotic crises.

Pioneered in Finland, the Open Dialogue process adopts a systemic approach, focusing on the whole family or network rather than just the individual. Key principles underpinning the approach include flexibility – ‘leaving models behind’ – continuity and tolerance of uncertainty. Results from non-randomised trials are striking; for example, almost three-quarters of people with 1st-episode psychosis returned to employment or full-time study within two years, despite significantly less use of medication and inpatient care. It is no exaggeration to suggest that, should the ongoing evaluation report similar results, the Open Dialogue approach could fuel a radical shift away from the dominant ‘medicate and support’ model of Western psychiatric services.

Throughout the first day, proceedings were skilfully chaired by Angela Woods and Joel Waddingham, a role that demands the knack of being able to think on your feet (unlike us presenters with our pre-prepared spiels).

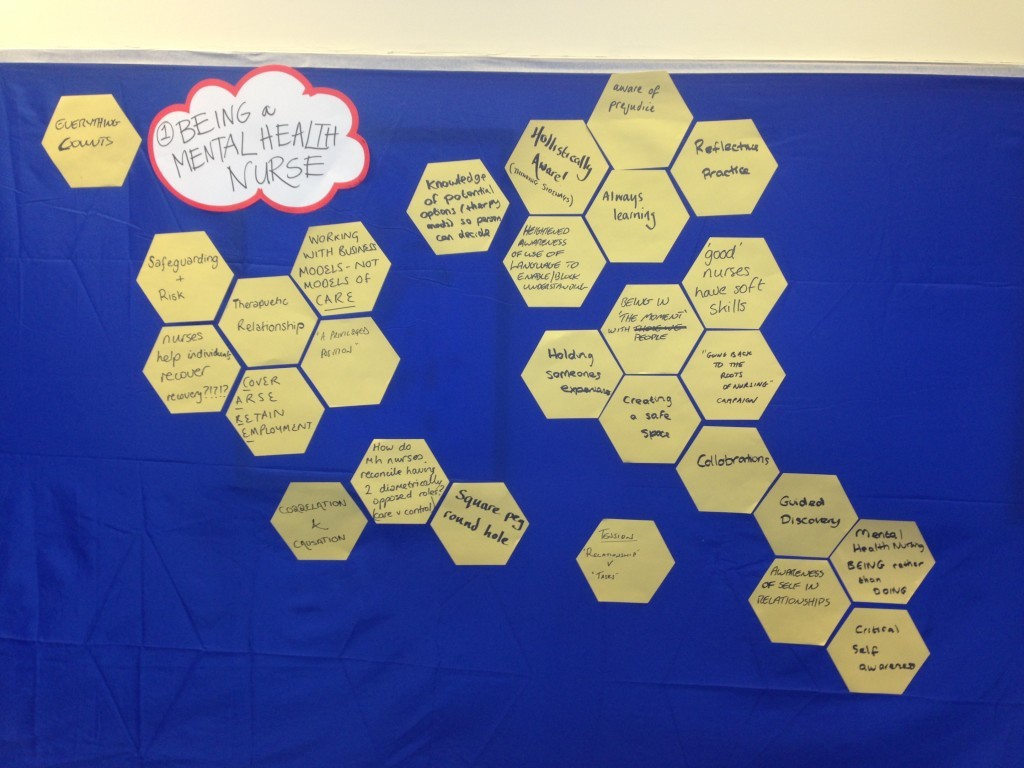

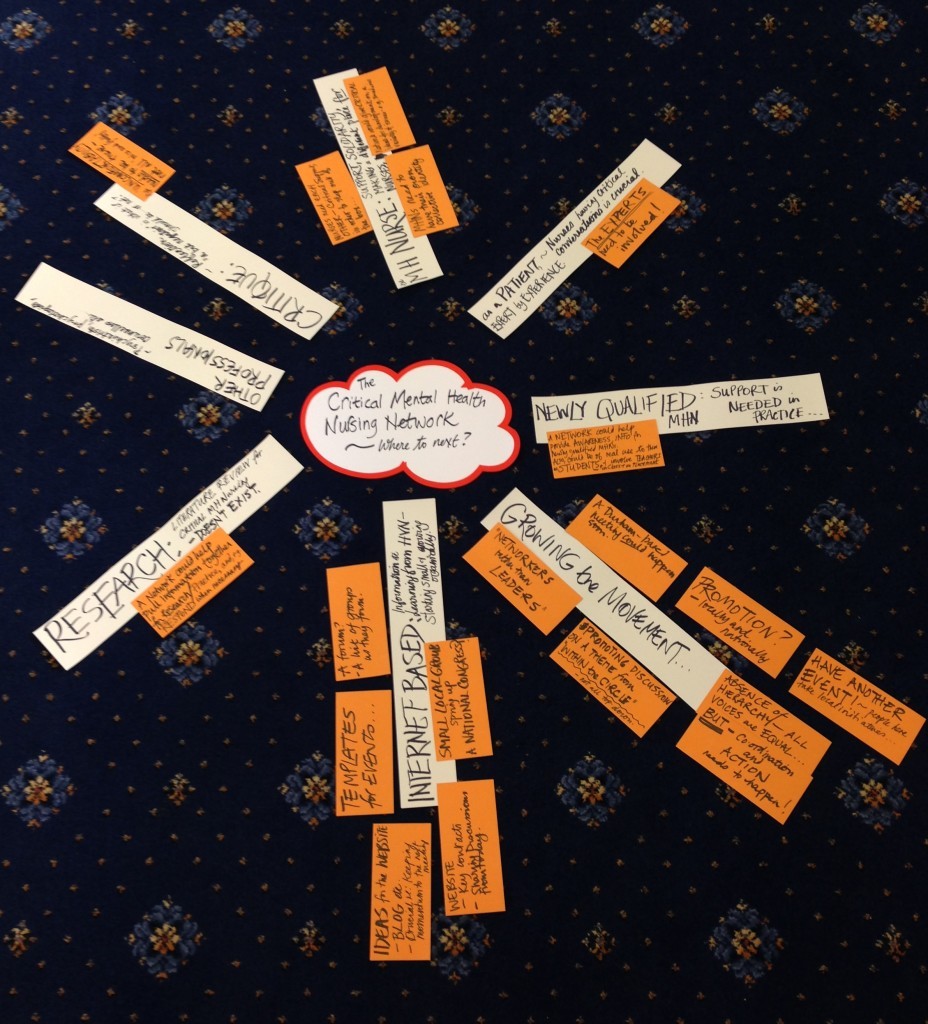

And so to the second day, a workshop with the expressed purpose of giving energy and direction to a newly-formed Critical Mental Health Nurses’ Network. Under the gaze of creative facilitator Mary Robson, we provoked, papped and pondered, our ideas on each theme captured on numerous sticky hexagons attached to a wall. With multiple statements on show, Mary would ask the whole group whether there was any item that needed clarification. On one occasion, I raised my hand and asked for an explanation of a ‘square peg in a round hole’ comment. The source of this wisdom turned out to be Sue, my wife; despite spending 33 years together, it is clear that I still struggle to understand her!

Throughout the conference I heard many moving personal stories. But one account from a service user – I won’t name her as I did not ask her permission to do so – stunned us all with its raw, emotional intensity. The lady in question vividly described how her victimisation at work triggered a descent into paranoia only for her to be further traumatised by the invalidating responses from psychiatric services. If ever I should flag in my efforts to change the way the Western world responds to human suffering, I will remember her story and feel re-energised.

Overall, it was an inspiring experience to mingle with motivated, like-minded people, all determined to improve the responses currently on offer to people with mental health problems. We might not all agree about the route to follow or the pace of change, but we all seek a broadly similar destination.

And the future? Joel Waddingham, Adam Jhugroo, Jonathan Gadsby and others will oversee the construction of the world’s first Critical Mental Health Nurses’ Network. Psychiatric nurses constitute by far the largest professional group within mental health services and, on the evidence of this conference, they are blessed with an abundance of innovative thinkers. The combination of bulk and brains should ensure a productive future.

Dr Gary Sidley

Tales from the Madhouse

Website

Twitter