On 23-24 April 2014, Hearing the Voice hosted a two-day workshop on ‘Voices, Visions and Hallucinatory Experiences in Historical and Literary Contexts’ at St Chad’s College, Durham, in collaboration with the Institute of Early Modern and Medieval Studies, the Centre for Medical Humanities and the Wolfson Research Institute for Health and Wellbeing. Facilitated by HtV arts-in-health advisor Mary Robson, the conference brought historians, psychologists, medical humanities researchers, and literary scholars together in order to explore various aspects of hallucinatory experience in the medieval and early modern period.

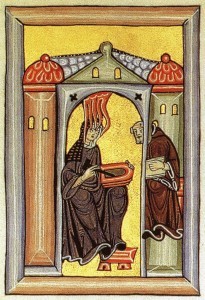

Corinne Saunders (Department of English Studies and Centre for Medical Humanities) opened the workshop with a brief introduction to the Hearing the Voice project and the aims of the next two days. She explained that “reports of phenomena redolent of hallucinatory experiences” permeate both the religious and secular literature of the medieval and early modern periods, suggesting that “the experience of hearing voices and seeing visions was, to a great extent, socially and culturally integrated.” This contrasts “starkly” with the present-day clinical model of hallucinations, according to which such experiences are “pathological symptoms of psychosis” requiring therapeutic, and often medical, intervention. By examining the way in which hallucinatory experiences were “described, regarded and explained” in medieval and early modern culture and society, Saunders continued, we can hope to gain a better understanding of how it is that these phenomena came to be seen as a symptom of illness rather than a meaningful feature of human experience.

What followed was a series of plenary addresses, panel presentations and small group discussions on the following key themes: cognition and sensory modalities; pathology; and inspiration and creativity. An early highlight of the workshop was Christine Cooper-Rompato‘s (University of Utah) discussion of the similarities and differences between accounts of visions and voices in medieval hagiographical literature and their present-day counterparts in various forms of online media. In addition to exploring the role saints ascribed to perceived location in discerning whether voices and visions had a divine or demonic source, Cooper-Rompato drew attention to the fact that, in many medieval accounts, hallucinatory experiences are represented as ‘fused’, involving visual, auditory, tactile and olfactory sensations. This contrasts sharply with clinical models of ‘psychotic’ hallucination, which tend to give primacy to a single sensory modality.

The emphasis on the multi-modal character of hallucinatory experience in medieval literature continued into Sarah Salih’s (King’s College London) presentation on the “kinetic dimension” of interactions with devotional art in Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love. We also heard from Johannes Depnering (University of Oxford) on fourteenth-century mystical experience and HtV postdoctoral research associate Hilary Powell. Drawing on examples from the hagiography of St Dunstan, Powell argued that accounts of demonic encounters in medieval literature are not “mere digressions” from the main narrative, nor do they serve simply to warn monastic readers of the dangers of demonic temptation in order to encourage proper religious conduct. Rather, representations of demonic visions and voices have what she calls a “cognitive utility” for their monastic audience: that is, by providing images that could be memorised and later recalled, they serve as an important “cognitive tool” for monastic readers, enabling them to “guard against mental distraction and intrusive thoughts.”

Jules Evans (Queen Mary, University of London) explored how reverie and other dissociative states can be an important source of inspiration and creativity for writers, and also considered the role of the poet as a “shamanic prophet”, channelling the spirit of the “tribe” or nation, and opening up access to a spiritual or higher world. Laurie Maguire (University of Oxford) also gave a fascinating presentation on the representation of voice-hearing in Christopher Marlowe’s Dr Faustus. Based on the German story Faust in which a man sells his soul to the devil in exchange for power and knowledge, the play was first published in 1604 (the A text) and then revised and re-issued in 1616 (the B text). Maguire explained that Faustus hears voices in both versions of the text. However, while the voices he hears in A are internalised (i.e. they are “echoes of self-generated thoughts”), the voices he hears in B are externalised and attributed to external sources (e.g. the devils). According to Maguire, the revisions introduced in the B text therefore have the effect of reducing Faustus’s inner life and agency and transferring his agency to external forces. This, in turn, reflects important changes in the early modern conception of the self and mind.

Overall, the workshop was a huge success, and Hearing the Voice would like to thank everyone who helped to make it so illuminating and inspiring. It was fascinating to hear your views on the multi-modal character of hallucinations, the links between early modern accounts of visions and voices and present-day trauma theory, and the role of memory in the generation of hallucinatory experiences. We hope that this will be the first in a series of workshops exploring the way in which hearing voices and other unusual experiences have been represented and interpreted in different cultural, religious and historical contexts, and look forward to continuing our research into how it is that this rich and enigmatic feature of human experience came to be pathologised.

For more information about the workshop, please download the Visions, Voices and Hallucinatory Experiences in Historical and Literary Contexts workshop programme.

Resources for conference participants are available here.